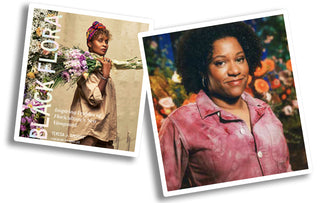

Since this blog was first published in the New York Times by Abra Lee, both Abra and Talia have been featured in the book Black Flora by Teresa Speight.

Following the Path of the ‘Invincible Garden Ladies’

By Abra Lee

My mama once offered a nugget of wisdom that changed the trajectory of my life: “Learn your garden history.” She didn’t mean the kind of history you typically find in books. She meant the kind that runs through your veins.

My mama once offered a nugget of wisdom that changed the trajectory of my life: “Learn your garden history.” She didn’t mean the kind of history you typically find in books. She meant the kind that runs through your veins.

Heeding my mama’s advice as I embarked on my journey to professional horticulture — a field that is predominantly white — I became consumed with discovering the success stories of Black people who’d laid the foundation that I was building upon.

During this time, I was introduced to women I lovingly call “the Invincible Garden Ladies.” Women like Bessie Weaver, who entered the flower business in 1911 and was recognized by the International Florists’ Association as the first Black florist west of the Mississippi; Blanche Hurston, who owned a wildly successful flower farm in Jacksonville, Fla., in the 1920s; and Annie Mae Vann Reid, a self-taught plantswoman and owner of a five-acre nursery and greenhouse who supplied customers across the United States with millions of seeds, flowers, shrubs, bulbs and vegetables from the 1920s until the mid-1960s.

At a time when few Black people, let alone Black women, were able to own thriving businesses, Mrs. Reid grew hers from a small plot in Darlington, S.C., to an empire worth about $1.2 million in today’s money. A champion of women and education, she advised students at schools such as Bennett College, a historically Black, all-female institution, teaching the floral business so women could set up their own shops.

For many of these women, gardening, and the independence it can yield, was not just about reaping for themselves what they had sown. It was about a future self-determination for a Black community that had for so long been unable to work the land in a way they chose.

For many of these women, gardening, and the independence it can yield, was not just about reaping for themselves what they had sown. It was about a future self-determination for a Black community that had for so long been unable to work the land in a way they chose. When you build a garden, you have to think ahead, nurturing the soil so it will continue to be fruitful for seasons to come. These women did that — both figuratively and literally.

Teresa Speight, owner of the Maryland horticultural business Cottage in the Court and author of the forthcoming book “Black Flora,” knows this firsthand. “Gardening requires reaching back into your DNA and paying attention to what your elders are telling you,” she said. A descendant of sharecroppers in North and South Carolina, Ms. Speight understands not just the physical benefits of nurturing a garden but the transformative power that cultivating the land can have.

“Each of us has these seeds of our ancestors sown into us. And each of us is growing that seed of that plant in our own way,” she said. When you begin to garden, there is “the instinct that our hands have met the soil before, and we know what to do with it.”

Dr. Wilfreta Baugh agrees. She is a longtime member of Our Garden Club of Philadelphia and Vicinity, founded in 1939 and believed to be the oldest continuously active Black garden club in the United States. “It’s like rearing a kid: You know that what you put in is what you get out,” she said.

The garden club works with local elementary school students — particularly those in food deserts, where access to fresh produce is limited — to pass their lessons on so that young people can build from the foundations of their work. “It is phenomenally important to plant the seeds for the next generation,” Lillian Harris Ransom, the club’s former president, said.

I often return to a line from Bessie Weaver’s 1915 speech to the National Negro Business League in Boston, where she spoke about the ways that cultivating plants could help Black women achieve independence. “Your flowers grow even while you are asleep, and the forces of nature are in a league with you in your endeavor to succeed,

As for me, I have tried my best to follow in the footsteps of these “Invincible Garden Ladies” — as a horticulturist, a historian, a manager and a mentor. I often return to a line from Bessie Weaver’s 1915 speech to the National Negro Business League in Boston, where she spoke about the ways that cultivating plants could help Black women achieve independence. “Your flowers grow even while you are asleep, and the forces of nature are in a league with you in your endeavor to succeed,” she said.

Mrs. Weaver understood the song that was singing in my heart, the one that my mama had instilled in me: that self-belief and knowledge will allow me to open doors for Black people.

When it comes to horticulture, this is our story. This is our song.

Author

Abra Lee is an ornamental horticulturist; founder of Conquer the Soil, which works to raise awareness of Black garden history; and author of the forthcoming book “Conquer the Soil: Black America and the Untold Stories of Our Country’s Gardeners, Farmers, and Growers.”

Lee, A., (2021, October 26). Following the Path of the ‘Invincible Garden Ladies’. The New York Times: Black Gardeners Find Refuge in the Soil Special Series. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/26/special-series/black-gardeners-pandemic.html